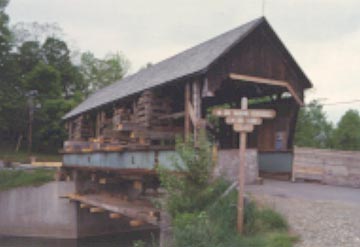

The Lincoln Gap Covered Bridge Renovation

WGN 45-12-15

There is a spurt of construction this year among Vermont's historic bridges.

North Bennington began reconstructing its Paper Mill Bridge last winter and completed the work July 7. The Mill Bridge in Tunbridge was opened to traffic with a celebration on July 22, the work begun early last spring. The reconstruction of the Fuller Bridge in Montgomery is well under way, completion slated for mid-September.

The historic covered bridge in Warren is also undergoing renovation. This bridge, built in 1880, features queenpost trusses of massive dimensions. The truss, long hidden from casual inspection, has been concealed by sheathing these many years.

The story of Warren and its covered bridge experience should be of great interest to the covered bridge community. When a town and its taxpayers have decided to do serious work on their bridge, how is it funded? Who does the work of the town in finding the funds? Where do you find the expertise to do the construction?

Jan Lewandoski won the contract for the work. He is the owner of Restoration and Traditional Building, a company specializing in historic preservation and the structural restoration of historic timber structures. He and his crew have been restoring covered bridges since the mid 1980's. He has restored 24 covered bridges including Town lattice, Burr arch, tied arch, kingpost, queenpost, Long and Paddleford types. He has built three new ones, with single spans as long as 147 ft. (Lowes Bridge, Guilford, Me.) and is presently starting on a fourth, an 80-foot lattice truss, for the Town of Hartland, Vermont.

I met with Jan Lewandoski and Phil Covelli, Assistant Administrator for the Town of Warren to get their stories: about the bridge, the work being done; and about how the town funded the work.

Photo by Joe Nelson

July 5, 2000

Monday, July 5, 2000

Phil Covelli: "In June '98, the AOT inspected all of the bridges up and down Mad River, and didn't find anything that was too serious with this one. We knew what needed to be done because of the study, but it wasn't closed to traffic at that point. It wasn't that bad. Then flood came and knocked off one of the fascia boards on the upstream side enabling us to see the beams. When we got a look at those we knew we had problems.

"I'm sure the flood didn't help it any. That low carrying beam has been rotting away for a [long time]-- did you see the rotten beam?"

Joe Nelson: "Yes, I took a photo of it. What got you started on funding this thing, was it after the FEMA report?"

P.C.: "The FEMA report didn't really show anything in relation to this bridge, we were really concerned with the house on the other side of the bridge that washed out. That was bought through the acquisition process with FEMA. The bridge right after the flood wasn't a concern. We knew it had to be done, but there wasn't an immediacy. Then come November, when AOT did another inspection of it, they closed it to vehicular traffic and that was it."

J.N.: "How do the local folk feel about the bridge, are they pretty much attached to it?"

P.C.: "We got a lot of support for it. Down stream there is a little waterfall there, a man-made dam. The town voted that year, 1998, to put $10,000 into a fund for a reconstruction effort for this and for the dam."

J.N.: "Was that to be matching money for whatever grant you could get?"

P.C.: "Could. For basic maintenance even if we had to cover it ourselves money-wise. No way did we expect the price tag we wound up with, we didn't know there was that much wrong with it.

"We approached the Agency of Transportation through what they called the bridge and culvert program. It's a program that has a $75,000 cap. The town pays 10 percent. Simultaneously we approached the Preservation Trust of Vermont which is underwritten by a lot of people in Vermont. The Freeman Foundation; we approached them to get some funding for this. We got those two funding sources together. This was in the fall of '98, that took until July of '99 just to get those two funding sources together. At that point Jan submitted a bid. Four bidders submitted a bid for the project. Jan had worked on the bridge before. The select persons were comfortable with his bid and his history. There's only a handful of these guys around, so word gets around who's good at it, and who is primarily a concrete bridge contractor.

"Once Jan submitted the bid, the board accepted it. He was ready to get started and he came down here and did further inspection and found out even more was wrong with it than the $75,000 that we had initially talked about.

"So we approached the AOT; Warren Trip and J. B. McCarthy. We proposed that since we were going to fix the bridge, and 75 percent of the work, the scaffolding, lifting the bridge up, what would be the sense in fixing it halfway and then six years later having to come back and lift the bridge back up to do the downstream side. Didn't make much sense. They agreed and the AOT came up with a special agreement were they will pay 95 percent of the cost up to $135,000. And the town would have to pay 5 percent. It gets a little confusing . We have one program, we pay 10 percent, and that $75,000 and the additional $35,000 or so is covered by another program which we pay 5 percent, then we have the Freeman Foundation/Preservation Trust money as well, so we're in good shape. So in total, we're looking at about $107,000 for this project."

J.N.: "Did you have to manage all this?"

P.C.: The AOT did a lot of this work and Jan did a lot of it, but getting the funding sources together, I brokered that more or less. It worked out well. It's unfortunate we had to wait this long for the bridge to be rebuilt but it was fortuitous that we were able to do it all at one time. The folks at AOT were really supportive of this whole thing. We don't have enough good things to say about these folks. They really came through for us.

Jan Lewandoski: "What we are doing here is mostly rebuilding the upstream truss which over the years had suffered some rot. That rot also occurring at the big windows which are located between the queen posts. Water running down from there rotted out the bottom part of the queen post and its connection to the bottom chord and rotted right through the bottom chord. It had been repaired, I don't really know when, with a splice across the bad part of the chord. Affixed with bolts and split rings, [it was] probably done by the state I'm guessing, quite a long time ago, at least 40 years ago I bet. It was getting worse, the carrying timbers had rotted and the floor was in danger of sagging, so the town and state decided to fix that truss of the bridge. When looking at it more, with the state Covered Bridge Committee and emeritus leader Warren Trip, we decided to take the bridge back closer to its original form. Over the course of time more joists and more carrying timbers have been added [to the bridge], and some metal work had been added to the outside of the queen post.

"The original [queen post] connection is a metal connection. One of the things people who look at historic covered bridges get confused about, they think everything was wood on these bridges. Pretty much only the lattice trusses, and Paddleford's truss depend totally on wood connections. With most of the other bridges, the tension connections are metal, even the oldest, the original bridges. The Colossus in Philadelphia of 1811 was filled with metal stuff, Theodor Burr's bridges are full of metal.

"In this bridge the original connection between the queen post and the chord was a wedge-tab dove-tail joint but there were no pins in the dove tail and its angle of slope over 12 inches was about an inch, so it wasn't really going to do any real holding. Two long bolts inside each queen post ran down through it, through the chord, and through the carrying timbers below it.

"At a later date, I'm not sure when, maybe in the 1930s or 40s, probably when motor vehicle traffic came on the bridge, the state added auxiliary brackets on the side of the queen posts with auxiliary rods, and I think they added more carrying timbers below, 10 x 12s. What we are going back to is probably the original carrying timber situation which was a pair of 12 x 14 timbers, in this case it would be hardwood timbers, oak or hickory, at each queenpost. And we are using bolts the same as the originals in the original positions, still keeping the auxiliary brackets; the state feels they are necessary for modern truck traffic, but we've got them snugged in closer, so we feel they'll work better and be less obvious too. The original tension connection of the queen post and chord on this bridge is an iron bolt, quite common in trusses at the time.

"You'll find it in churches; bridges aren't the only trusses in the state, the attics of all the churches are filled up with trusses, and many town halls. Some of them quite old, some from the 18th century. You'll find variations from building to building; sometimes the dove tailed joint, usually with a gang of pins, sometimes a big tenon with a gang of pins. It really depends on how much load is on the connection between the chord and the queen post. Other times it's metal U-straps or they'll use a metal bolt on the inside, frequently original to it. Go to the middle ages, and you'd find metal at the bottom of kingpost trusses for tension joinery.

"In the floor in this bridge: we're changing the carrying timbers; we'll have the floor joists out; we're going to replace any bad stringers or those made of built-up lumber with solid 10 x 12 stringers that go from the carrying timbers to the abutments or from carrying timber to carrying timber. And this bridge had been given a nail-lam 2 x4 deck recently. It wasn't in terrible shape but was getting worn. The worse thing about nail-lam in general is that it is un-repairable. You can't take apart a nail-lam deck, you've got to destroy it to do anything, even to inspect the bridge. So we're going over to 3-by plank laid transversely across the bridge, across the stringers, and on top of the 3-by plank, two- and-a half-inch hardwood runner plank lagged down. Hopefully that will keep the vehicles in the center anyhow. I doubt if the bridge had runner plank originally, but it probably had 3 or 4 inch transverse plank. It didn't have nail-lam for sure.

"We are repairing the end-posts with scarf repairs in the bottoms, changing the bottom chord and putting on bed timbers which it hasn't had for a long time but it probably originally had., white-oak 10 x 12s with a span of 10 to 12 feet at each abutment, will spread load around and which are sacrificial, so that if rot occurs it doesn't rot up into the chord, it'll rot the bed timber and white oak resists better, although no wood resists totally."

Photo by Joe Nelson

July 5, 2000

This was the bottom of one of the upstream queenposts. Notice the adz and broad- axe marks

Photo by Joe Nelson

July 5, 2000

A compression splice in an end-post.

Photo by Joe Nelson

July 5, 2000

Warren's Lincoln Gap Bridge raised for repairs.

Photo by Joe Nelson

July 5, 2000

Queenpost to chord tension joint. The hole above the state-mandated bracket accesses the internal bolt.

Photo by Joe Nelson

July 5, 2000

"We are replacing the original with an identical member: a 12" x 12" x 56 ft. single stick of white spruce that I acquired in the Northeast Kingdom, the largest single stick of natural timber I have ever installed," said Jan Lewandoski.